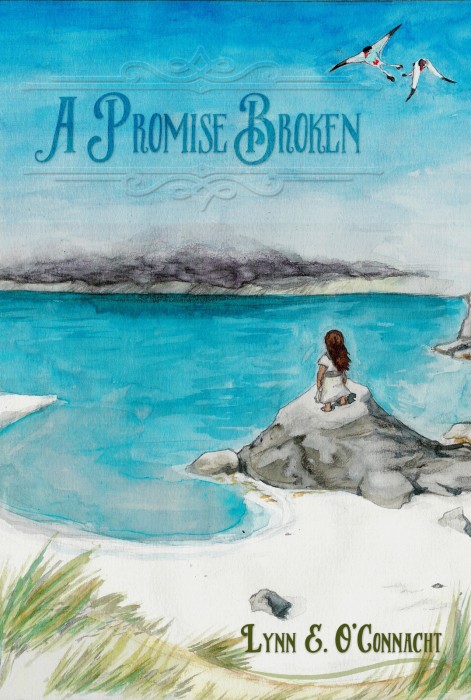

You may remember Lynn from the book discussion we had last month on Some Kind of Fairy Tale. She recently released her novel A Promise Broken, which first appeared in serial form on her blog. In honour of the occasion, I have invited her to share a bit about her experiences with serialised fiction.

Serialised fiction isn’t a new concept. One of the earliest forms of serial fiction may be The Tale of Genji (源氏物語) written in the 11th century, but it is uncertain whether the novel was published in instalments. In Western society, serialised fiction was made popular in about the 19th century, though novels such as Tristram Shandy were already being published in volumes a little before this time. More, ah, traditional examples of serialised fiction authors include Charles Dickens, Alexandre Dumas, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Poetry could also be found published in serialised form, such as Lord Byron’s Don Juan.

The rise of serialised fiction in the West coincided with several societal changes that made fiction more widely available. Simplistically seen, these changes all stem from the Industrial Revolution and many of them still influence us to this day. The Revolution is when compulsory school attendance laws were passed and, in the UK, when local boroughs could start their own free library. Paper (and thus books and magazines) became easier and cheaper to produce.

My point is that serialised fiction isn’t a new concept. The internet, fanfiction and the prevalence of mobile devices have reintroduced us to the format. Like in the Industrial Revolution, the rise of serialised fiction coincides with large changes to our (Western) society. Fans were among the first to embrace these new technologies to write stories and produce digital art. Today serialisation is especially popular among indie authors as well as webcomic artists and, still and ever, the fans who write fiction.

When I started writing long-form for others to read myself in my mid-teens, it was in serialised form. I published pieces as they were finished and, taking on board feedback, would sometimes start over from scratch if something wasn’t working and I’d figured out how to fix it. I published my works for my friends to read and to learn the craft more than anything else. It’s how I met some of my closest friends, like Elizabeth.

Serialising A Promise Broken as a Work-In-Progress was, in some ways, a return to my digital writing roots with the biggest difference that, this time, I wouldn’t be releasing instalments as I finished them but on a schedule. I’d wanted to serialise it as a complete penultimate draft that needed only some mild typocatching starting this year. Running the serial last year was not part of my plan, but idealism and activism ensured that I did. Diversity in our fiction is important. You need only look at projects like Jim C. Hines’ Invisible (now in its second year ) to see how important. The decision to serialise a year early, before I was even done writing the story, followed on an especially awful few months in terms of diversity and representation. (I spoke a little about my reasoning before starting the project.) The story wasn’t done; it wasn’t ready; I’m sure I messed up somewhere. But sharing it was something that I could do as a budding indie-author that I felt might, someday, make a difference to someone.

However, the choice to serialise an unfinished work wasn’t ideal for me. I’m not the fastest writer and I discovered fairly early on that I needed to restrict myself to one post per week to be sure I didn’t have to take any breaks. I’d never done a structured serial before. Other people will have other answers on what works, of course. Faster writers can easily produce three posts per week or even daily!

As far as challenges go, writing speed wasn’t a large factor for me. I caught on to the fact that I was being too ambitious early on. A far bigger challenge was the fact that A Promise Broken wasn’t written to be serialised. Sometimes it proved impossible to find a good transition point between instalments. I’d set the average at between 1,000-1,500 words as that seemed to be the sweet spot for the serialised fiction I’d seen and while less than that isn’t necessarily an issue, much more than that is. Much longer than 1,500 words and people stop reading.

The chapters of A Promise Broken average at about 3,500 words, so roughly every three instalments on the website made up one chapter. Transitions in between them weren’t always as smooth as they could be. Either I picked the wrong paragraph to cut off or information was missing. One of the things that serialising fiction can teach a person is how to write smooth transitions. Reading a story in instalments may highlight issues that reading in one go won’t catch for you.

Sometimes my instalments were just too long for reading comfort. Once, I did that on purpose: in December, when other year-long serials I’d seen had wrapped up their narrative for the year and offered shorter bits of fun and fluff for the holiday hiatus. I bumped up the word count, so that the serial would finish before the Christmas holidays. Obviously, if you publish in a cultural sphere which celebrates other feasts, you may find yourself doing this at different times.

Currently, I’m at work on the sequel to A Promise Broken, which I aim to start serialising in 2016. It still won’t be written specifically for serialisation, but any future serialisation projects I do most likely will be. I’ve got a few ideas, some of which are ideally suited to the format because they’re episodic in nature.

Lyn Thorne-Alder has written a basic (but wonderful) guide on starting your own webserial here .

I’d also like to leave you all with a small list of others authors who produce serialised works :

Elizabeth Barrette (specialises in serial poetry)

Pia Foxhall (features explicit content and is not suitable for all readers)

M.C.A. Hogarth

LB Lee

Clare K.R Miller

K.A. Webb

Sarah Williams

And Shadow Unit is a webserial produced by several authors.

This is not an exhaustive list, of course. There are many authors producing serial works, but hopefully these will give you a good idea of the kinds of stories out there.

And you can find more serialised fiction via sites such as:

http://webfictionguide.com/

http://muses-success.info/

Lynn E. O’Connacht has an MA in English literature and creative writing, but wouldn’t call herself an authority on either. She currently resides on the European continent and her idiom and spelling are, despite her best efforts, geographically confused, poor things. Her tastes are equally eclectic, though fantasy will always be her first love. She has been chasing stories one way or another since she was old enough to follow a narrative.

2 thoughts on “Guest post: On Serialised Fiction”

Comments are closed.